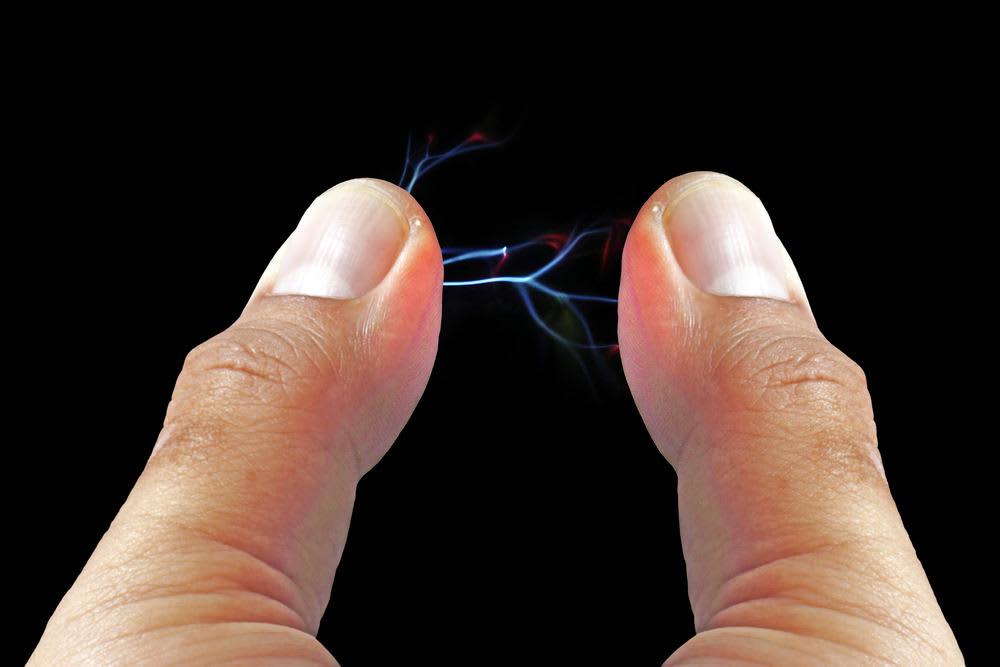

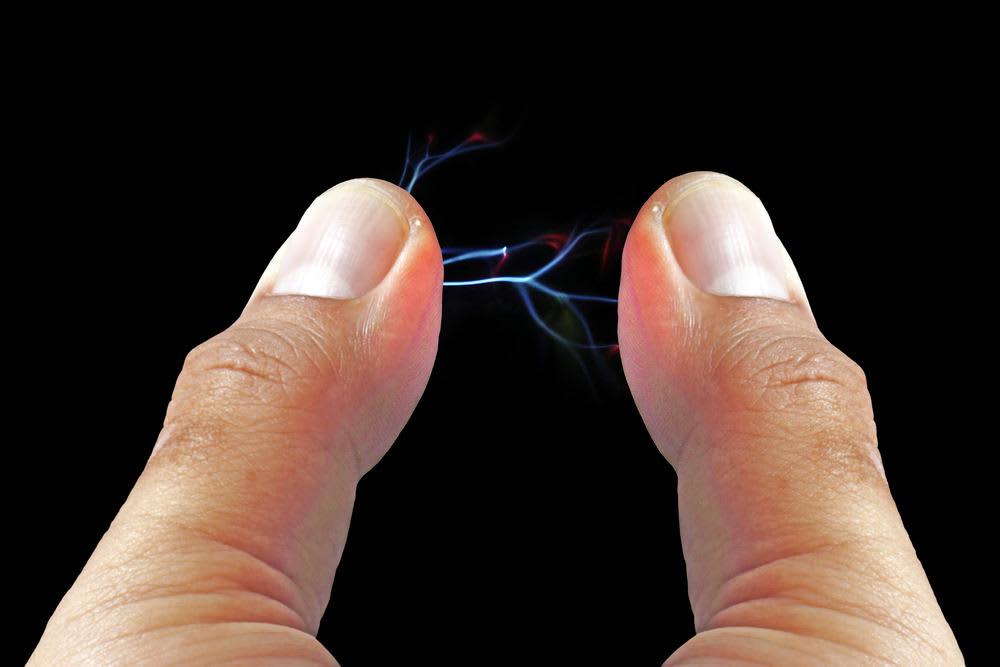

Have you ever found driving to be positively shocking? For example, you have just driven a long distance on a cold, wintry day, in a car with leather-covered seats. Wearing a heavy woolen coat, you get out of your car and, as you put your hand onto the metal door handle, “ZZZZzzzztttt!” - a jolt of static zaps your finger with pain. You have just been shocked by your car door.

Why you get shocks from your car

Winter, leather seats, woolen car coats and car doors all conspire on super-cold wintry days to deliver static shocks that can run up to 300 volts or more. At that level, the jolt is pretty good; at night you should be able to see the blue spark leaping from your hand to the metal. Even a tiny 100-volt jolt is enough to cause you to wince.

You might wonder why it happens. The reason involves the differential potentials of materials in your car. Wool is a natural static electricity generator as is leather. As you slide across your car’s leather seat to get out and go on your way, your coat, rubbing on the upholstery, builds up an electrical charge. Your car’s body remains at ground, or negative charge.

Since static discharges usually happen from positive to negative, the charge that has built up on you and your clothing naturally wants to seek a ground path, it uses the first contact it finds with your car’s body, usually you hand. That’s why you feel the zap.

There are three external factors that make winter the prime time of year for static shock:

- Cold temperatures

- Low dew point

- Super dry air

Winter air is naturally quite dry because cold temperatures drive moisture out of the air. As the air gets colder, more moisture is driven out, lowering the dewpoint substantially. The air, in turn, becomes even drier. This is a great environment for static as the dry, cold air with low dewpoints encourages static electricity buildup.