A sway bar (also called an anti-sway bar or anti-roll bar) is a component of some vehicles’ suspensions. You might guess that “sway” in a car or truck isn’t a good thing, so an anti-sway bar would be useful, and in the broadest terms that’s correct. But it’s also a bit more complicated than that.

To understand the function and purpose of a sway bar, it’s helpful to consider what other parts comprise a vehicle’s suspension and what they do. Every vehicle suspension includes:

Wheels and Tires. Tires provide traction (“grip”) that allows the car to accelerate, decelerate (slow down), and turn. They also absorb the shock from small bumps and other road irregularities.

Springs. Springs protect the passengers and cargo from larger bumps.

Shocks or struts. While the spring cushions the jolt when a vehicle hits a bump, the shock absorber or strut, a cylinder filled with a thick oil, absorbs the energy from the same bump, which causes the vehicle to stop bouncing.

Steering system. The steering system translates driver inputs from the steering wheel into back-and-forth movement of the wheels.

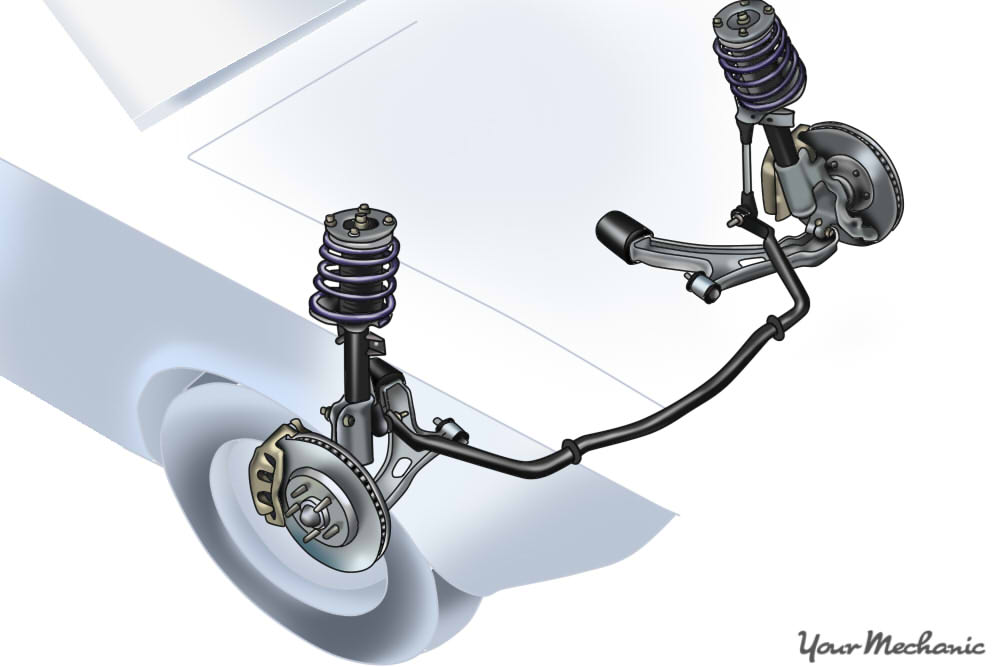

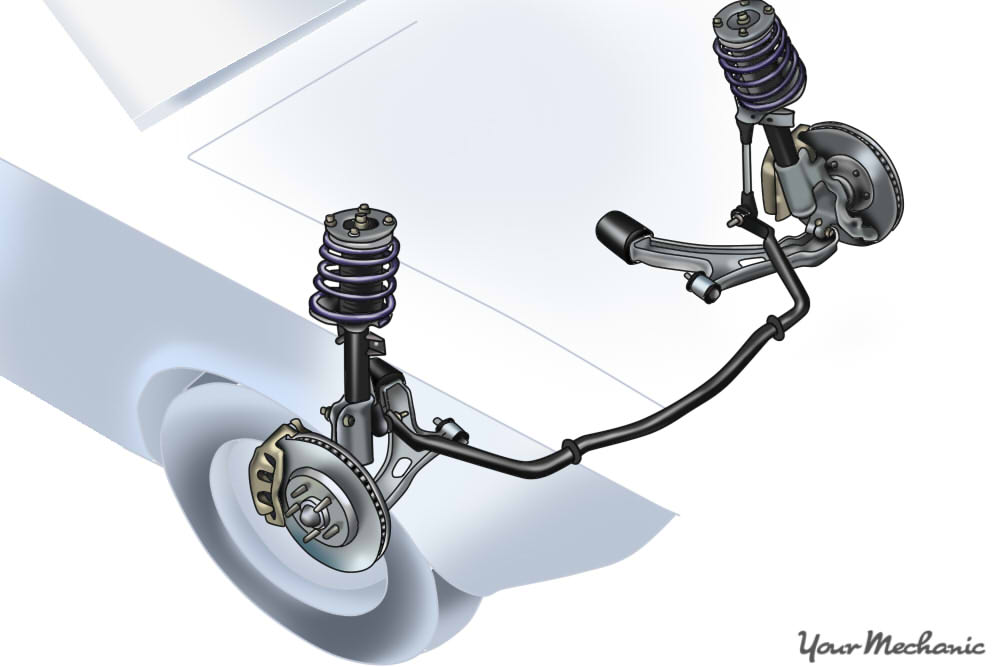

Linkages, bushings, and joints. Every suspension includes numerous linkages (solid parts such as control arms and other rods) to keep the wheels properly positioned as the vehicle moves, and bushings and joints to connect the linkages while allowing the right amount of movement.

Notice that “sway bar” doesn’t appear on that list, because some cars don’t have one. But quite a few do, so let’s delve a little further. What does a sway bar do that the parts listed above don’t do?

The purpose of a sway bar

The answer goes back to that guess above, that a sway (or actually anti-sway) bar tends to keep the car from swaying (or more precisely, from leaning to one side or the other). That is what a sway bar does: prevent body lean. A sway bar does nothing at all unless the vehicle is inclined to lean to one side, but when it does start to lean (which usually means the vehicle is turning — every car or truck tends to lean to the outside of a turn), the sway bar applies force to the suspension on each side, upward on one side and downward on the other, that tends to resist the leaning.

How a sway bar works

Every sway bar is a torsion spring — a piece of metal that resists twisting force. The sway bar is attached at each end, one end to one wheel and at the other end to the opposite wheel (both fronts or both rears) so that in order for the wheel on one side to be higher than that on the other the bar has to twist. The sway bar resists that twist, tending to restore the wheels to the same height, and the vehicle to level. That’s why a sway bar does nothing unless the body of a vehicle leans to one side: if both wheels rise (as they would when the vehicle hits a bump) or fall (as at a dip) at the same time, the sway bar doesn’t have to twist, so it has no effect.

Why use a sway bar?

For one thing, it can be uncomfortable, disconcerting, or even dangerous for a vehicle to roll too much in turns. More subtly, uncontrolled body roll tends to cause the wheels’ alignment, and in particular their camber (tilting inward or outward) to change, reducing how well they can grip the road; limiting body roll also tends to keep camber controlled, meaning more consistent grip for braking and turning.

But there are downsides to installing rigid sway bars. One is that when a vehicle hits a bump on just one side, it has the same effect on the suspension as body roll: the wheel on one side (the side that hit the bump) moves upward relative to the body of the vehicle, while the other doesn’t. The sway bar resists this movement, applying force to keep the wheels at the same height. So a car with a stiff sway bar that hits such a bump will either feel stiffer (as if it had very stiff springs) on the side with the bump, will lift the tire off the road on the other side, or both.

Vehicles that encounter high turning forces and in which maximizing tire grip is critical, but that tend to be driven on smooth roads, tend to use large, strong sway bars. High-powered cars like the Ford Mustang are often equipped with thick front and rear sway bars, and even thicker and stiffer bars are available on the aftermarket. On the other hand, off-road vehicles like the Jeep Wrangler, which need to be able to negotiate large bumps, have less rigid sway bars and dedicated off-roaders sometimes remove their bars entirely. The Mustang feels solid on the track and the Jeep stays poised in rough terrain, but have them change places and neither performs as well: the Mustang feels much too rough over rocky terrain while the Jeep rolls easily when turned hard.